Egyptian novelist and first Arab Nobel laureate who

sprang to world attention with his depictions of life in Cairo's old city

|

| Google image |

"The square has had many scenes," he said. "It used to be more quiet. Now it is disturbing but more progressive, better for ordinary people - and therefore better for me also, as one who likes his fellow humans."

-Mahfouz on Cairo's central Tahrir Square, 1990

Denys Johnson-Davies

Guardian - Wednesday 30 August 2006

The Egyptian novelist Naguib Mahfouz, who has died

aged 94, was the Arab world's most prominent literary figure. Neglected in the

west, modern Arabic literature achieved international recognition when Mahfouz

was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1988, and it is difficult to think of any winner

of the prize whose status as a writer was so dramatically changed as that of

Mahfouz by the award.

From being a writer known only in the Arab world and

to a handful of Orientalists, he sprang to world attention. Whereas previously

no major publisher in England or America was prepared to publish his work,

overnight he was taken up by a leading American publishing house and became a

bestseller. His novels were then quickly translated into many languages.

Born in Gamaliya in the old city of Cairo, the son of

a minor official, the writer spent his first years in the distinctive medieval

atmosphere with its narrow lanes, clustered overhanging buildings and

picturesque artisans. Its features became part of his consciousness and are

brought to life in some of his early realistic novels and, more particularly,

in The Cairo Trilogy on which, both in the Arab world and in the west, his fame

in great part rests.

Mahfouz's life was ordered and singularly devoid of

variety or dramatic happenings - if one is to exclude the 1994 assassination

attempt by a young extremist from which the writer miraculously escaped with

his life. He received a traditional education at a kuttab (Koranic school),

then at primary and secondary schools, where he read many of the great works of

classical Arabic literature and mastered the Arabic language with its

complicated grammar and syntax. Having graduated in philosophy from Cairo

University in 1934 he then began an MA in philosophy, which he abandoned when

he decided to make a career of writing.

Realising that writing must inevitably be part-time,

he joined the civil service until his retirement in 1971. Among the posts he

held were director of the film censorship office and, finally, adviser to the

culture minister. On into the 1980s, Mahfouz supplemented his income by writing

film scenarios, yet while more than 30 films were made from his novels, he

refused to adapt his own work for the screen.

On his retirement he joined the group of distinguished

writers, among whom was the playwright Tawfik al-Hakim, at Egypt's leading

newspaper al-Ahram. From then on his novels were first serialised in the pages

of the newspaper before being brought out in book form. Having perforce to earn

his living as a civil servant, Mahfouz acquired the necessary discipline to

organise his time so that he would be able both to read widely and to produce a

considerable corpus of fictional writing. Even feeling that marriage might

prove a hindrance, he delayed marrying until the age of 43.

He wrote more than 30 novels. His first attempts were

three novels with Pharaonic backgrounds, the first being The Curse of Ra

(1939). Next came a period of social realism as seen in novels like Midaq Alley

(1947), an entertainingly vivid depiction of the alleyways of his youth and the

extraordinary characters that inhabit them: the hashish-smoking cafe-owner

Kirsha, and Zaita, the "fashioner of deformities", who performs

maiming operations on those wishing to take up a life of begging.

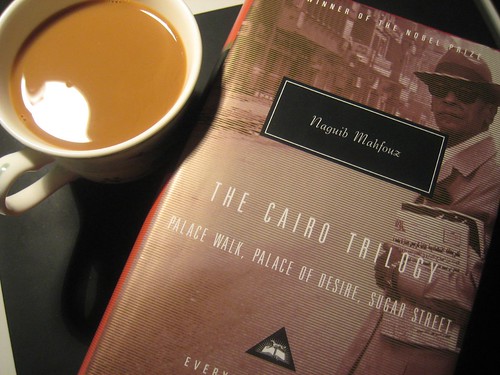

Then, in 1956, Palace Walk, the first volume of The

Cairo Trilogy, came out, to be followed a year later by the other two volumes,

Palace of Desire and Sugar Street. A novel on the grand scale of some 1,500

pages, the trilogy deals with three generations of the Abd al-Jawad family and

extends from 1917 to just before the end of the second world war.

During this time Egypt was engaged in a struggle for

independence from British rule. The three volumes describe in minute detail the

daily events in a middle-class Egyptian family, recording for history as no

other book does, a way of life that has disappeared under the impact of western

influence and the pressures of modern life. The political happenings of the

times are interwoven into the lives of the many characters. Members of the

protagonist family represent the main trends in the political life of the

country: the Wafd party, with its heroes Saad Zaghloul and Mustafa Nahhas (the

party with which Mahfouz associated himself), the burgeoning socialist movement

as exemplified by the writings of Salama Mousa, and the beginnings of a

fundamental Islamic movement.

The myriad characters and events are handled with

great skill and the writer is seen throughout to be in complete control of his

material. It was a remarkable achievement, in particular when one bears in mind

that the Arabic novel had only recently come into being. The Trilogy quickly

became a bestseller in the Arab world, and those who could not read it came to

know its characters through the films that were made of it; that it could also

be appreciated outside its own cultural confines is shown by the fact that in

the United States the Trilogy achieved sales of more than 250,000 copies.

Though not published until 1956-57, the Trilogy was

completed before the 1952 revolution of Gamal Abdul Nasser. Mahfouz was

disillusioned by the revolution and the repressive era that it introduced.

Unable to criticise it, he preferred to remain silent. Then in 1957 he started

work on Children of Our Alley (which was translated into English as Children of

Gebelawi). It was the novel that brought its author into conflict with Egypt's

religious authorities. After its serialisation in al-Ahram, al-Azhar, Cairo's

religious university, refused to allow the work to appear in book form. In a

society with religious susceptibilities, exception was taken to a novel dealing

with issues that were considered not acceptable subjects for fiction. Later the

novel came out in Beirut and until today is available in Egypt only under the

counter. Many years later it became the reason for the attack on his life on

October 14, 1994, in which he was hospitalised with a wound to the neck,

leaving him partially paralysed in his right arm.

The novel shows a departure in his approach, being

written in an episodic form, a form that he was to adopt later in other works.

While the themes that preoccupy him often repeat themselves, Mahfouz continued

throughout his career to seek new techniques. Children of Our Alley is an

allegory in which God appears in the character of Gebelawi, Adam as

"Adham", while other characters represent the prophets Jesus and

Muhammad. Though a new translation was published by the American publisher

Doubleday in 1996, a decision was taken not to make it available in Egypt.

Other novels which are of particular interest include

The Harafish (1977): it too is written in episodic form and takes place in an

alleyway of Cairo's old city. It deals with several generations of the same

family, universalising the alleyway into an image of the human condition. The

myth here is of his own invention, unlike his use of the fall of Adam in

Children of Our Alley.

Mahfouz was widely read in western fiction and

particularly admired Flaubert, Stendhal, and Proust, and Melville's Moby Dick.

His borrowings from the west in matters of technique can be seen in his novel

Miramar (1967), published in 1967, in which - following Lawrence Durrell's

Alexandria Quartet - he relates the story of several characters staying in a

pension in the seaside city of Alexandria, recounting the same incidents from

the point of view of four different characters. The book was published in

English in 1978 with a perceptive introduction by John Fowles who, at this

relatively early date, saw in Mahfouz "a significant novelist".

Published in 1979 and then in English in 1995, Arabian

Nights and Days is yet another novel to be written in the episodic form which

Mahfouz came to favour. In it he chooses tales from the classic Thousand and

One Nights and reforges them into narratives dealing with those themes that

have always occupied him: good and evil, man's social responsibility, and,

increasingly with time, death. The novel is set in an Arabian Nights

atmosphere, but many of the issues relate to Egypt's present problems: the

corruption of those in power, social justice and the rise of the fundamentalist

movement.

Hardly had Miramar appeared when the Israeli victory

in the 1967 six-days war, a defeat that was as humiliating as it was

unexpected, rocked the Arab world. Mahfouz's reaction was to give up writing

novels for five years.

During this period Mahfouz added to the total of 14

volumes of short stories that he published, often with stories of singular

blackness that matched his mood. His contribution to the Arabic short story is

often forgotten in the face of his overwhelming achievement in the novel. Among

his collected works in English is a single volume of stories under the title

The Time and the Place (1992). One of the stories represented in this volume,

Zaabalawi, has found itself included in the Norton Masterpieces of the World as

the only piece of Arabic writing, apart from some extracts from the Koran. His

very first at writing fiction were short stories, which he was delighted to

find being accepted and appearing in print. He recounts how one day an editor

asked him to pass by the office. He did so and was handed a pound for his

latest story. "One gets paid as well!" exclaimed the budding writer

in disbelief.

His last novel was Qushtumar (1988) and his last

published work was another collection of short stories, The Seventh Heaven

(2005) which dealt with the afterlife. He wanted, he observed, to believe that

something good would happen to him after his death.

Mahfouz also rendered Arabic literature a great

service by developing, over the years, a form of language in which many of the

archaisms and cliches that had become fashionable were discarded, a language

that could serve as an adequate instrument for the writing of fiction in these

times.

Neither the fame nor the considerable monetary reward

afforded by the Nobel Prize altered his life. He continued to live in his

modest flat in the middle-class district of Agouza with his wife and two

daughters and changed nothing in his daily routine. He remained until the day

of his death, by then a frail old man with failing sight and hearing, a modest

man with a ready smile and that sense of humour for which Egyptians are famous.

John Ezard writes: In 1990, when he was a physically

wasted, half-blind yet zestful 79-year-old, I interviewed Naguib Mahfouz in the

Ali Baba cafe overlooking Cairo's central Tahrir Square, where he breakfasted

for 40 years and which he had seen change from a Nile-side preserve of the rich

to a demotic chaos. "The square has had many scenes," he said. "It

used to be more quiet. Now it is disturbing but more progressive, better for

ordinary people - and therefore better for me also, as one who likes his fellow

humans." Any country is fortunate if it produces citizens like him.

·

Naguib Mahfouz, writer, born December 11 1911; died August 30 2006

No comments:

Post a Comment