US immigrant Ted Ngoy built a dynasty of flour and sugar that changed the fate of hundreds of his fellow countrymen seeking a better life. A sudden addiction took it all away, but it left him all the wiser decades later

BY CHRIS WHITE

23 JUN 2018

NOW in his twilight years, Ted Ngoy takes a moment to reflect on his unconventional life. “I think I’ve made a little difference to the world,” he says humbly with a chuckle.

The 77-year-old changed the lives of Cambodian refugees flooding into the United States during the nation’s civil war in the 70s and 80s. He wasn’t handing out money or houses, but did it another way. Making doughnuts.

Ngoy was affectionately known as the ‘Donut King’ in America, starting an empire from scratch, and employing hundreds of his fellow countrymen, who often arrived penniless into strange surroundings. His influence spread, inspiring thousands of Cambodians to open doughnut shops, and cash in on America’s enduring love for the sugary treat.

In the early 2000s, the advent of health-driven diets could have been the kiss of death for the calorie-laden doughnut, but it never lost its appeal, especially in America, where the nation consumes more than US$40 billion worth of deep-fried dough a year.

It’s also becoming a staple in Asia, brought on by Western influences and time-deprived societies seeking fast-food solutions. Asia-Pacific is the world’s fastest-growing region for doughnuts, with over US$6 billion in sales. By 2024, that’s predicted to grow to US$9.5 billion, second only to the US.

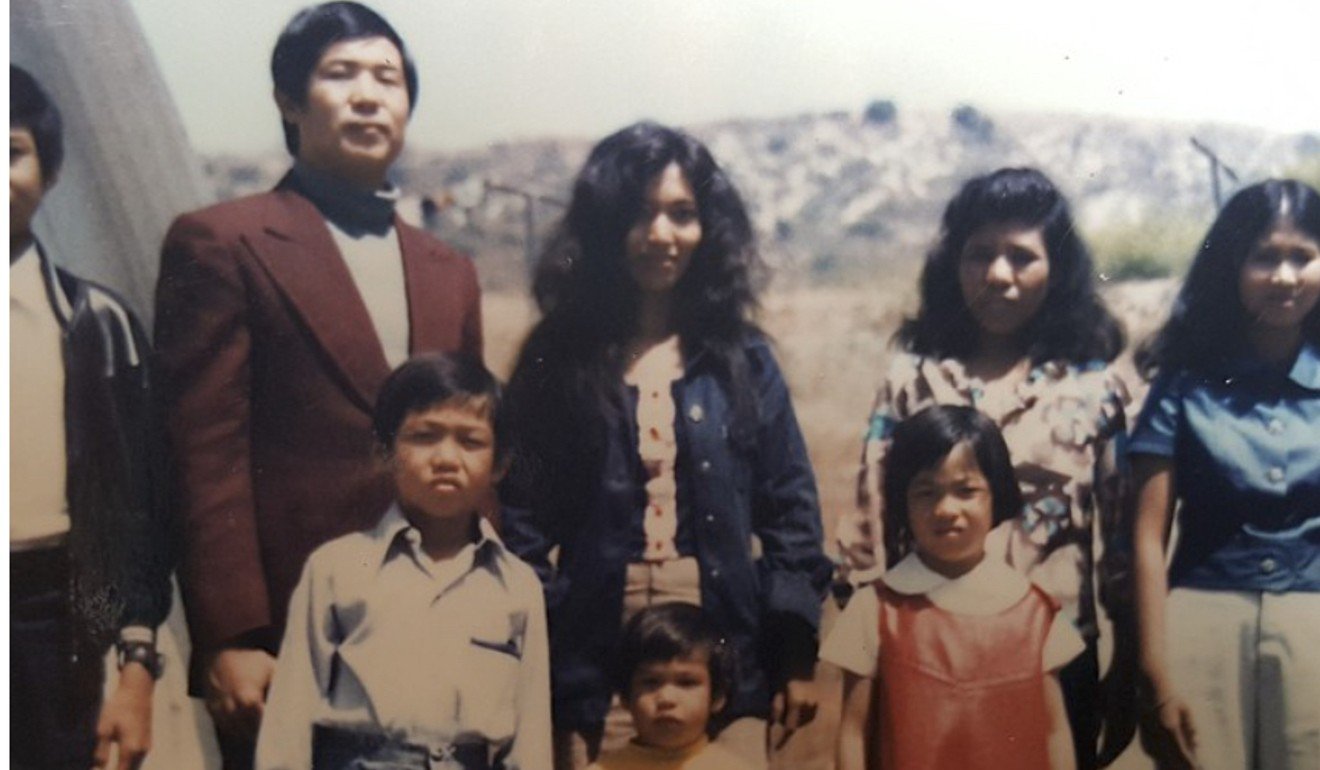

Ted Ngoy with his former wife Suganthini and children not long after arriving in the US. Photo: Ted Ngoy

Today, the eponymous doughnut brands of Dunkin’ Donuts and Krispy Kreme dominate the global landscape, but barely make a dent in California, where it is estimated that 90 per cent of the 5,000 doughnut stores are Cambodian-owned. Ngoy and his dough-making comrades have kept them at bay for more than four decades.

As anti-US feeling grows in Cambodia, China cashes in

“In 1990, there were nine Dunkin’ Donut stores in southern California, but [they] couldn’t push for any more, as the Cambodians make the best fresh doughnuts and American citizens love them,” says Ngoy.

“In 2000, they tried a second time. But they need big locations, huge stores, so rent is more expensive and they make high volumes to compensate the high expenses. But ‘mom and pop’ Cambodia stores can make low volume, take better care of the customer and cherish their doughnuts. They can’t beat us.”

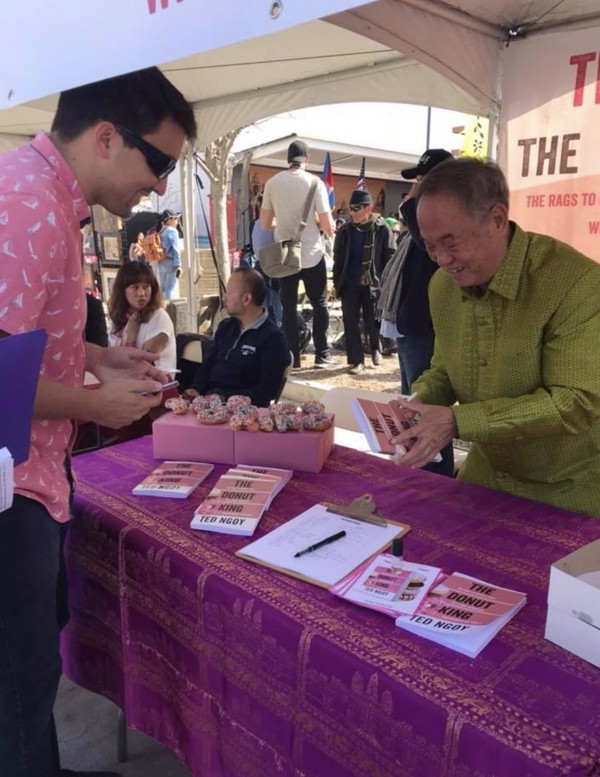

Now Ngoy is publishing his autobiography, T he Donut King: The Rags to Riches Story of a Poor Immigrant Who Changed the World.

Donut King Ted Ngoy holds a book signing event in Long Beach, California. Photo: Ted Ngoy

His story begins in the early 1970s when Ngoy was a commander in the Royal Cambodian Army, training soldiers in Thailand. After a civil war broke out and Phnom Penh fell to the communist Khmer Rouge, Ngoy knew his life was in danger, so took his wife Suganthini and three children to the US in 1975.

“We were in a refugee camp. We had nothing, but we were lucky. We got one of the last planes allowed out of the region to Los Angeles before Pol Pot put a stop to it,” he says.

Parishioners at the local Peace Lutheran Church in Tustin, Orange County, raised money for refugees and sponsored Ngoy’s work visa, giving him a job and a house. “I cleaned the church, mowed the grass, that sort of thing. But it was barely enough to get by, so I asked my sponsor to find me another job, and they found one at a Mobil service station.”

Why does sunny Cambodia attract such shady characters?

Working through the night as a petrol attendant had one advantage – he could watch the goings-on at the local doughnut store opposite, sometimes going in and chewing on their food, which reminded him of the sugary pastries back home. The Donut King was hooked.

“I asked them what it takes to run a shop like that? I wanted one. They said: ‘You’re crazy, you don’t know anything about the business. How can you bake, run a store? What do you know?’”

He knew very little, but was an eager learner and found a trainee job with a bigger doughnut chain, Winchells. “They said ‘we don’t hire Asians’, but I begged them to take me. They trained me on how to run a store, payroll, recruitment, and each month I kept saving. Asians love to save,” he says.

A customer heard Ngoy was on the lookout to operate his own shop, and showed him a local newspaper advert for a doughnut store called Christy’s in nearby La Habra. It was advertised for US$45,000, Ngoy was US$5,000 short, but they were happy for someone to take the ailing business off their hands.

Hun Sen counts on China as he cracks down in Cambodia: has he miscalculated?

“By now I knew the secret. All these big companies just make one doughnut batch at night, then let them stay there all day, so they get old. I always advise people to make small batches throughout the day, that’s the secret, to keep them fresh, carefully watch every doughnut you make,” he says.

His formula proved to be a huge success, and his reach grew. He’d buy failing stores on the cheap, often sitting in his car watching the trade come and go, before deciding on his offer.

In March, Ted Ngoy went to the US and visited some of his old Cambodian friends who own doughnut stores. Photo: Ted Ngoy

By 1980, he had opened 20 stores and was employing dozens of Cambodian refugees, sponsoring their work visas. In the next five years, he would help many more settle in the country, train them in doughnuts and management, and make them lessees under the Christy brand. He also came up with the idea of pink boxes, which are now synonymous with the dessert.

“Anybody who wrote to me for help, I’d speak to the US embassy in Bangkok, as I was very friendly with them. They’d see my name and let them come. We trained them, then leased them a doughnut shop. I encouraged them to take care of themselves, I’d loan them money, then give them the store, train them by the hundreds. We wanted everyone to benefit and earn money for a living,’ says Ngoy.

“I can help a hundred people set up in business, but each one was employing mothers, sons and daughters, while other relatives were also being supported. We were helping thousands in the end, and opening stores everywhere from Oregon to Texas.

“We kept on expanding, I could have made more money, but I was still making US$100,000 a month. Now there’s at least 4,900 Cambodian doughnut store owners in California alone.”

Ngoy also took an active role in the community and grass roots politics. He was the Asian-American Republican Chairman of California and raised money for the Tea Party.

Workers at one of Ted Ngoy’s stores in 1970s California. Photo: Ted Ngoy

In 1991, George HW Bush went to California to give Ngoy a presidential award for his contribution to the socio-economic success of the American-Cambodian people. “It was for living the American dream. I was very proud. I also met Ronald Reagan and Richard Nixon. They liked my doughnuts, everyone did,” laughs Ngoy.

But even as business was booming, Ngoy wasn’t always happy and a friend suggested he take a break.

“I was making a lot of money but didn’t know how to enjoy my life, so one day someone came to see me and said I should see Elvis Presley in Las Vegas. I said ‘where’s Vegas?’ I went once, then a second and third time, I was hooked.”

This led Ngoy to gambling, and it proved to be a costly mistake in more ways than one.

“I saw these people gambling on blackjack and I told my wife ‘let’s have some fun’. So at first it was five dollars, then 10. The more I went, the more I was addicted. I feel so much remorse. I think the most I lost was US$1 million, but, it wasn’t the money. I had no time for the business, my family, relatives and friends, you lose everything. In the end, I lost my wife.”

To beat his gambling addiction, Ted Ngoy went to Buddhist monasteries in Washington and Thailand, Neither time worked and he returned to gambling. Photo: Ted Ngoy

Ngoy tried various things to beat his addiction, first joining a Buddhist monastery in Washington, where he even shaved his head and lived a solemn life for a month. Next, he went to a monastery in Thailand, thinking he was miles from temptation, but when he came back to the US, he hit the gambling tables again.

It was around this time, in 1993, when Cambodia was having its first free elections, and he thought about running for office. “I sold the stores, gave some money to my children, then went back to Cambodia. I just wanted to open the American dream to the Cambodian people. I wanted to tell people my story. I wanted to help build peace and democracy.”

Ted Ngoy at home in Phnom Penh. Photo: Ted Ngoy

Later, Ngoy moved to the costal town of Kep, Cambodia, spending the next few years drifting around. By the early 2000s he’d been introduced to Christianity, eventually kicking his gambling habit, and started making money from real estate. “I turned myself to Jesus. I completely quit gambling. I believe and love in Jesus. He saved me,” he says.

Now Ngoy spends his time dabbling with property investments in Phnom Penh and visiting his children and friends, who all run doughnut stores in California, and often seek his advice.

But mostly he’s relaxing. “I’m 77, I’ve been working for 70 years, it’s chill time for me now.”

He’s had the odd nightmare, but Ngoy’s always lived in the spirit of the American dream.

No comments:

Post a Comment