The ‘death of democracy’ cements the military’s power in politics – and paves the way for the prime minister’s succession plan

BY DAVID HUTT

4 AUG 2018

this week in asia

Cambodian strongman Hun Sen’s supposed sweeping victory in the last weekend’s heavily rigged general election is set to cement the role of the country’s armed forces in politics and pave the way for his son’s rise to power.

Although official results won’t be announced until the middle of this month, the ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) spokespeople have publicly said it took roughly 80 per cent of the popular vote and won all 125 seats of the National Assembly. If true, it would consolidate the party’s complete domination over Cambodia’s political institutions. The CPP already controls all but four seats in the country’s upper house after senate elections in February, and holds roughly 95 per cent of all elected positions at the local level.

The latest victory was hardly a surprise given that the only viable opposition party, the Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP), was dissolved last year. Most of its politicians are now in exile. Its leader, Kem Sokha, remains in pre-trial detention after his arrest in September on treason charges. Several democratic nations, including the United States, called the election illegitimate and the CNRP’s vice-president Mu Sochua described the result as the “death of democracy” in Cambodia. But it could portend an even more alarming future.

Mu Sochua, vice-president of the Cambodia National Rescue Party. Photo: Reuters

Paul Chambers, a lecturer at the College of Asean Community Studies at Naresuan University in Thailand, said the result could spell “the further militarisation of Cambodia’s parliament and Cambodian politics in general”, allowing Hun Sen to transform himself into a “Napoleon, overseeing a camouflaged military autocracy”.

Three of Cambodia’s most senior military figures ran for parliament on the CPP ticket last weekend. Pol Saroeun, the former commander-in-chief of the Royal Cambodian Armed Forces, was a candidate in Preah Sihanouk province. Meanwhile two former armed forces deputy commanders-in-chief, Meas Sophea and Kun Kim, ran for office in Preah Vihear and Oddar Meanchey provinces, respectively.

The three were the primary candidates in each of the provinces, according to the CPP’s official candidate list. That means that if the party has won all 125 seats in the National Assembly, as it says it has, then these officials will be sworn in as parliamentarians this month. Abiding by the law, they temporarily resigned their military posts in May so that they could campaign for political office.

Cambodian General Pol Saroeun with US Defence Department official Robert Jones. Photo: AP

Since coming to power in 1979, when it helped overthrow the Khmer Rouge regime, the CPP has maintained a close, even symbiotic, relationship with the country’s military. Most senior military officials sit on the party’s Central Committee, and some on its more exclusive Permanent Committee. But recent elections have seen military officials become far more involved in formal politics, with an increasing number of former generals becoming provincial governors and securing elected positions in local administrations.

Also competing in last weekend’s election was Chey Son, secretary general of Cambodia’s National Authority for Chemical Weapons, while Dy Vichea, deputy chief of the National Police and Hun Sen’s son-in-law, was a reserve candidate. Former armed forces commander-in-chief Ke Kim Yan, who now serves as a deputy prime minister and chairman of the National Authority for combating Drugs, stood for re-election in Banteay Meanchey province. Although Hun Sen removed him as the military chief in 2009, he is understood to maintain considerable influence among rank-and-file soldiers.

At least five other senior ex-military officials also ran for office either as the main or reserve candidates in different provinces, according to the CPP’s candidate list.

Cambodian former armed forces commander-in-chief Ke Kim Yan with the deputy commander-in-chief of the US Pacific Command David Bramlett. Photo: AP

Days before the election, the US House of Representatives passed the Cambodia Democracy Act, which could bar US companies from doing business with sanctioned Cambodian officials, and freeze their assets in America. It must pass the country’s Senate before sanctions can take effect.

Kun Kim, who has been dubbed “Hun Sen’s hatchet man” for his role in post-election violence in 1998, and Pol Saroeun were included in a list of officials who could be sanctioned. They were also included in Human Rights Watch’s recent “Dirty Dozen” report, which detailed human rights abuses allegedly committed by the Cambodian military. So far, only Hing Bun Hieng, the commander of Hun Sen’s personal bodyguard unit, has had sanctions imposed on him by the US government. These were meted out under the Magnitsky Act.

Hing Bun Hieng, the commander of Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen’s bodyguard unit. Photo: Reuters

Sophal Ear, an associate professor of diplomacy and world affairs at Occidental College at Los Angeles, suspects some of the senior ex-military officials didn’t choose to run for political office. Instead, their retirement was requested by Hun Sen. As committed loyalists, they would no doubt serve as effective whips and enforcers for Hun Sen within parliament, while maintaining their influence within military circles. Moreover, they could take positions on important committees within the National Assembly, such as those that decide military affairs and budgetary matters.

Cambodia’s election: against Hun Sen, only way to win is to not vote

Constitutional change may soon be at hand, some observers believe. Political analyst Meas Nee told local media Cambodia could introduce reforms similar to Thailand and Myanmar, where the military is guaranteed a certain number of seats in either the National Assembly or the Senate.

Retiring senior generals allows Hun Sen to promote more loyalists through the military ranks, analysts say. When Pol Saroeun stepped down in May, the acting commander of the armed forces position was handed to Sao Sokha, an armed forces deputy commander and commander of the National Military Police. He has been one of Hun Sen’s closest aides for decades, earning notoriety after comparing his success as a military official to the tactics used by Adolf Hitler.

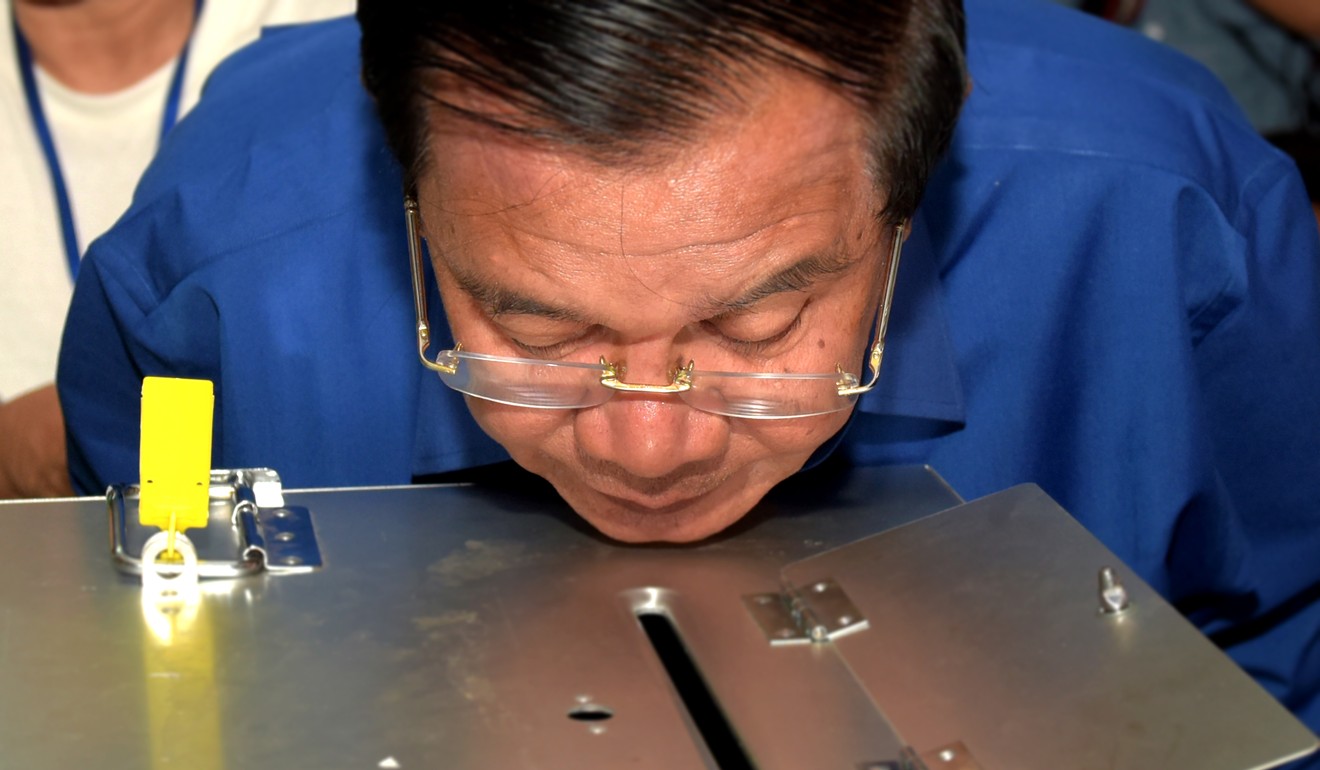

Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen looks at a ballot box after taking part in what was widely seen as a rigged election. Photo: AFP

But the biggest gain was made by Hun Sen’s eldest son Hun Manet, who is already an armed forces deputy commander, head of the counterterrorism task force and deputy commander of his father’s feared bodyguard unit. In June, he was appointed acting chief of the joint staff and acting chief of the armed forces, the positions vacated by Kun Kim and Meas Sophea. As such, further militarisation of Cambodian politics could be designed to lay the groundwork for Hun Sen’s possible succession. Most analysts’ money is on Hun Manet.

“Hun Manet already controls the armed forces, Hun Sen’s bodyguard unit, the military police, the secret police, the anti-terrorist unit. Isn’t it already a military regime?” Mu Sochua said before the election.

“After the end of Hun Sen, there would likely be a grouping of senior military with Hun Manet as a figurehead,” Chambers said. As such, having military elites sitting in parliament would provide greater stability to this possible succession plan. ■

2 comments:

Keep going Okhna CHAM KHOY Hun Many.

The Hun family will go to hell soon.

Pourk Ah Chor Prey blood suckers.

Post a Comment