06 September 2020

Say Mony

VOA Khmer

Cambodian soldiers await the end of an airstrike by U.S. planes in the background before advancing toward a palm grove off route 4, south of Phnom Penh, June 13, 1973. (AP photo)

WASHINGTON D.C. —

An agreement to convert Cambodia’s contentious wartime debt to the United States to development aid or which would forgive the sum would substantively improve US-Cambodia relations, analysts and observers say.

The issue, at times, has been prickly over the years.

In the instance of Washington and Hanoi, an agreement to resolve Vietnam’s debt accrued to the U.S. during the same era was eventually reached through negotiations.

In the early 1970s, the U.S. lent around $270 million to Cambodia’s Lon Nol-led government, which had deposed head of state Norodom Sihanouk, to purchase food and agricultural commodities. The loan was made under a USAID program called Food for Peace, according to The New York Times.

While the United States was providing this relief for food and clothing for displaced persons and refugees, it also dropped around 500,000 tons of bombs on eastern Cambodia in a large bombing campaign from 1969 to 1973, as part of its’ attempt to cut off supply routes for the Viet Cong in neighboring Vietnam, according to a study by scholars Taylor Owen and Ben Kiernan published in the Asia-Pacific Journal in 2015.

Since the 1980s, the Cambodian government led by Prime Minister Hun Sen has refused to pay off the debt and interest and instead called it ‘dirty debt,’ asserting the U.S. owed a ‘moral debt’ to Cambodia for the destruction caused during the Vietnam War.

Arend Zwartjes, a spokesperson for the U.S. Embassy in Phnom Penh, said the U.S. believed that countries that “get into debt” should have to pay back the loans.

“That’s an issue that we’ve tried to work on over the years and sometimes we made progress,’’ Zwartjes said. ‘’But, certainly, that’s one of the issues we would like to have resolved.”

U.S. embassy employees sit in tuk-tuks, decorated with American flags, and kick-off activities marking 70 years of Cambodia-US relations in a parade along the streets in Phnom Penh, 2020. (Photo courtesy of U.S. Embassy in Cambodia)

The U.S. Embassy in Phnom Penh in recent months has undertaken an extended celebration to mark the 70th anniversary of U.S. relations with Cambodia, with a concerted social media and news media initiative to highlight many aspects of bilateral cooperation.

Analysts say the wartime debt remains a sore point as efforts continue this year to improve the bilateral relations that have been contentious for more than three years.

In 2017, the U.S. renewed calls for the debt to be repaid, though the context seemed to be fiscal prudence. Hun Sen appealed to U.S. President Donald Trump for debt forgiveness, but little came of the request.

At the same time, Prime Minister Hun Sen’s senior officials were using a so-called ‘color revolution’ narrative to justify a severe crackdown on political opponents and civil society groups and freedom of expression. At the crux of this claim was the allegation that the U.S. was helping the opposition party overthrow the Hun Sen government.

Ou Virak, the founder of public policy organization Future Forum, said the U.S. should raise the debt issue with Cambodia in a way that ensured an acceptable solution for both sides. He said it was important to remember that Cambodia was a victim of the Cold War, with the nation caught between global superpowers in the 1960s and 1970s.

Analysts say the wartime debt remains a sore point as efforts continue this year to improve the bilateral relations that have been contentious for more than three years.

In 2017, the U.S. renewed calls for the debt to be repaid, though the context seemed to be fiscal prudence. Hun Sen appealed to U.S. President Donald Trump for debt forgiveness, but little came of the request.

At the same time, Prime Minister Hun Sen’s senior officials were using a so-called ‘color revolution’ narrative to justify a severe crackdown on political opponents and civil society groups and freedom of expression. At the crux of this claim was the allegation that the U.S. was helping the opposition party overthrow the Hun Sen government.

Ou Virak, the founder of public policy organization Future Forum, said the U.S. should raise the debt issue with Cambodia in a way that ensured an acceptable solution for both sides. He said it was important to remember that Cambodia was a victim of the Cold War, with the nation caught between global superpowers in the 1960s and 1970s.

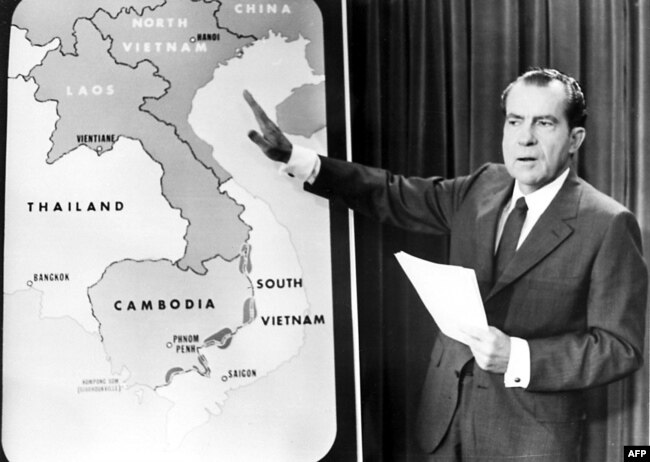

U.S. President Richard Nixon in the White House after his announcement to the nation on April 30, 1970, that American ground troops had attacked, at his order, a communist complex in Cambodia. Nixon pointed to the area of Vietnam and Cambodia in which he said the action took place. (AP photo)

“The debt ought to be talked about in the sense of [Cambodia being] a victimized country,” said the Cambodian-American analyst in Phnom Penh. ‘’To find ways to cancel it or convert it into aid, to reconnect the U.S.-Cambodia relations.’’

Ou Virak said one way this could be achieved was by the U.S. providing more scholarships to Cambodian students or by increasing American investment and aid in the education field, which would help foster closer bilateral relations.

Chheang Vannarith, president of Asian Vision Institute and a Cambodian foreign policy specialist, suggested the way forward is talks.

“Regarding the debt issue, both sides should resume their negotiations and convert it into development aid,’’ Chheang Vannarith said. ‘’Meaning that Cambodia could make the payments back to the U.S. and later turn them into aid [to benefit Cambodia].”

Sok Touch, president of the Royal Academy of Cambodia and a personal advisor to Hun Sen, noted the issue is challenging and that Cambodia has informed the U.S. that steps toward the conversion of the debt to aid and to set up a premium education program would be the best chance for a solution.

The U.S. Congress, in its reconciliation efforts with Vietnam, established the Vietnam Education Foundation in 2000 that provides scholarships for Vietnamese students wishing to study in the U.S. and provides an exchange of professors to teach in the Southeast Asian nation.

Hanoi also signed an accord with the U.S. in 1997 to pay $140 million in debt from the same Food for Peace program in 20 annual installments. Vietnam did not agree to pay back millions of dollars’ worth of military assistance provided to South Vietnam.

Ou Virak said one way this could be achieved was by the U.S. providing more scholarships to Cambodian students or by increasing American investment and aid in the education field, which would help foster closer bilateral relations.

Chheang Vannarith, president of Asian Vision Institute and a Cambodian foreign policy specialist, suggested the way forward is talks.

“Regarding the debt issue, both sides should resume their negotiations and convert it into development aid,’’ Chheang Vannarith said. ‘’Meaning that Cambodia could make the payments back to the U.S. and later turn them into aid [to benefit Cambodia].”

Sok Touch, president of the Royal Academy of Cambodia and a personal advisor to Hun Sen, noted the issue is challenging and that Cambodia has informed the U.S. that steps toward the conversion of the debt to aid and to set up a premium education program would be the best chance for a solution.

The U.S. Congress, in its reconciliation efforts with Vietnam, established the Vietnam Education Foundation in 2000 that provides scholarships for Vietnamese students wishing to study in the U.S. and provides an exchange of professors to teach in the Southeast Asian nation.

Hanoi also signed an accord with the U.S. in 1997 to pay $140 million in debt from the same Food for Peace program in 20 annual installments. Vietnam did not agree to pay back millions of dollars’ worth of military assistance provided to South Vietnam.

U.S. Ambassador W. Patrick Murphy speaks about U.S.-ASEAN relations to more than 100 students at the Institute of Foreign Languages of Royal University of Phnom Penh, in Cambodia, February 20, 2020. (Photo courtesy of U.S. Embassy in Cambodia)

U.S. Ambassador W. Patrick Murphy, in an interview with VOA Khmer late last year, said around 600 students from Cambodia study annually in the U.S., and that he would like to help significantly increase that. He was not referring to the conversion of the debt into an education program.

“In order to consider options like that, we would really need to have those discussions with the Cambodian government,” said Zwartjes, referring to a potential scholarship program emanating from the outstanding debt.

Cambodian government spokesperson Phay Siphan, Cambodian People’s Party spokesperson Sok Eysan, and Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesperson Koy Kuong declined to comment on the issue. They referred queries to the Ministry of Economy and Finance.

Kim Sopheak, a spokesperson at the Finance Ministry, responded via Telegram text message, saying that the latest position of the Cambodian government was to demand a complete cancellation of the debt because it had been considered “odious debt.”

Chhang Song, information minister under the Lon Nol administration which received the debt in the 1970s, said the loan issue was complex. He said there was no written agreement prepared at that time, outlining the conditions of the debt.

“In order to consider options like that, we would really need to have those discussions with the Cambodian government,” said Zwartjes, referring to a potential scholarship program emanating from the outstanding debt.

Cambodian government spokesperson Phay Siphan, Cambodian People’s Party spokesperson Sok Eysan, and Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesperson Koy Kuong declined to comment on the issue. They referred queries to the Ministry of Economy and Finance.

Kim Sopheak, a spokesperson at the Finance Ministry, responded via Telegram text message, saying that the latest position of the Cambodian government was to demand a complete cancellation of the debt because it had been considered “odious debt.”

Chhang Song, information minister under the Lon Nol administration which received the debt in the 1970s, said the loan issue was complex. He said there was no written agreement prepared at that time, outlining the conditions of the debt.

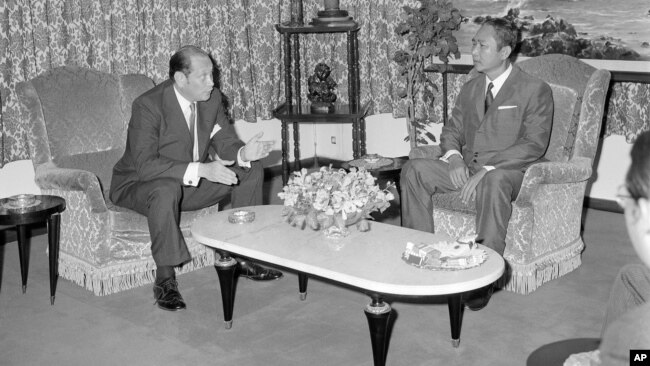

New U.S. Ambassador to Cambodia, John Gunther Dean, confers with Cambodian President Lon Nol after presenting a credential letter in Phnom Penh on April 5, 1974. (AP photo)

“Was it a loan or aid? Nothing was clear,” he said in a phone interview from Long Beach, CA., where he currently resides.

“Why? Because the Vietnam war was so huge that even just a [little] aid spilling over from South Vietnam was sufficient for Cambodia,’’ Chhang Song explained. ‘’So, there was no word of a loan but aid.”

If Cambodia owes wartime debt to the U.S., the debt should be converted into humanitarian aid for Cambodian citizens because Cambodia was a victim of the war, Chhang Song said.

Officials in Washington D.C. at the Departments of State and Treasury were not available for comment on the issue. U.S. State Department officials have said in the past that Cambodia had been able, yet unwilling, to make payments against the debt and that only lawmakers in the U.S. Congress could decide changes to the debt status.

Sebastian Strangio, author of the book ‘Hun Sen’s Cambodia,’ said the resolution of the debt issue would require a considerable shift in the bilateral relationship, especially given the current political situation in Cambodia. He indicated no one should hold their breath for this matter to be resolved.

“It will require Hun Sen to retire or move on or finish up his tenure and for new leadership to perhaps take a different perspective on the repayment of the debt,” Strangio said.

“Why? Because the Vietnam war was so huge that even just a [little] aid spilling over from South Vietnam was sufficient for Cambodia,’’ Chhang Song explained. ‘’So, there was no word of a loan but aid.”

If Cambodia owes wartime debt to the U.S., the debt should be converted into humanitarian aid for Cambodian citizens because Cambodia was a victim of the war, Chhang Song said.

Officials in Washington D.C. at the Departments of State and Treasury were not available for comment on the issue. U.S. State Department officials have said in the past that Cambodia had been able, yet unwilling, to make payments against the debt and that only lawmakers in the U.S. Congress could decide changes to the debt status.

Sebastian Strangio, author of the book ‘Hun Sen’s Cambodia,’ said the resolution of the debt issue would require a considerable shift in the bilateral relationship, especially given the current political situation in Cambodia. He indicated no one should hold their breath for this matter to be resolved.

“It will require Hun Sen to retire or move on or finish up his tenure and for new leadership to perhaps take a different perspective on the repayment of the debt,” Strangio said.

1 comment:

Rustic one five, Rustic one five, This is Hotel One-Three, do you read over?

Post a Comment